Overview

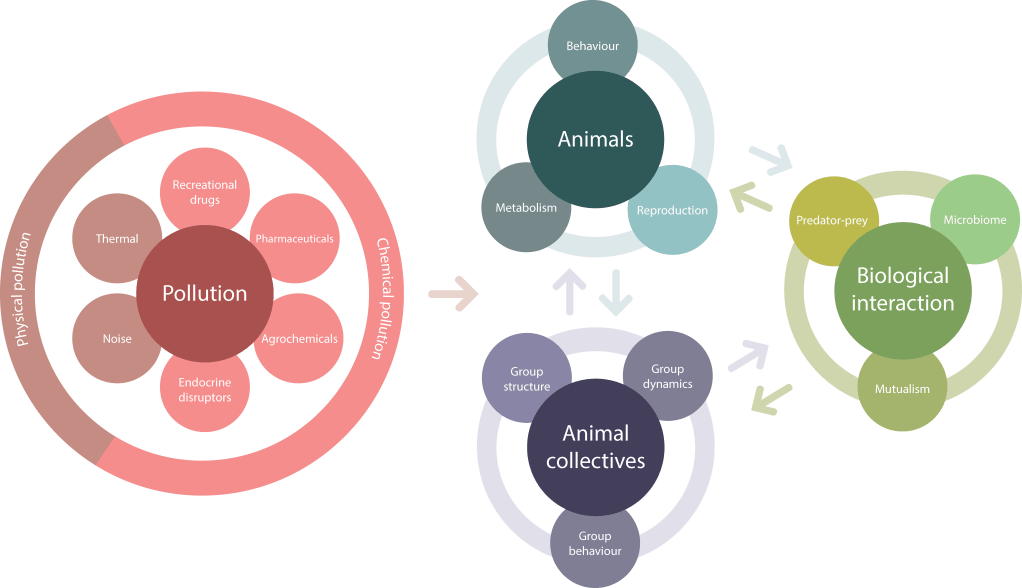

My research takes an integrative approach to understanding the impacts of human-induced rapid environmental change on wildlife. Primarily, my research focuses on the ecological effects of emerging chemical pollutants in aquatic ecosystems. Environmental contamination with synthetic chemicals is recognised as one of the fastest-growing agent of global change, with fears that we are operating beyond the planetary boundary for this global issue. A key challenge is to determine if, how, and when emerging pollutants affect wildlife and ecosystem function. My research program addresses this challenge through an integrative ecotoxicological approach structured around three interlinked research streams: (1) Behavioural ecotoxicology, (2) Evidence synthesis in ecotoxicology, and (3) Ecotoxicology of host-microbiota interactions, which in combination scale across taxa, systems, and disciplines.

Behavioural ecotoxicology

Animal behaviour has emerged as a critical tool in measuring chemical-induced impacts. The growing use of behaviour in ecotoxicology is primarily a result of its sensitivity to chemical disruption and its direct link to population-level outcomes. Concerningly, many emerging pollutants—particularly pharmaceuticals (e.g. antidepressants, anxiolytics, and endocrine disruptors)—have the potential to alter the behaviour of exposed wildlife. Indeed, there is now a building body of evidence, including my own work, reporting that environmentally realistic levels of emerging pollutants can disrupt a range of important behaviours in wildlife. Within the research theme of behavioural ecotoxicology, there are two principal sub-themes around which I am building my research: collective behaviour, and lab to field.

Collective behaviour: can a single individual tell the collective story

Most animals live in a social environment, from highly structured societies, to loosely structured social groups, and anything in-between. Thus, social interactions are group formation are fundamental for the survival of many species. Despite this, the majority of research in ecotoxicology focuses on the behaviour of individual animals, and seldom considers how chemicals might affect animal collectives and the interactions between them. My work asks whether emerging pollutants can disrupt the formation and composition of animal groups, and how this might affect collective behaviour. The figure on the left shows a group of 5 fish that have exposed to a neuroactive pollutant; the 5 points represent each individuals centroid position, the lines represent the distance from their group centroid (cohesion), and the yellow circle represent the group leader at any given time (Martin et al. unpublished data)

- Michelangeli M, Martin JM, Pinter-Wollman N, Ioannou- CC, McCallum ES, Bertram MG, Brodin T. Predicting the impacts of chemical pollutants on animal groups. (2022) Trends Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2022.05.009 | PDF

- Martin JM and McCallum ES. (2021) Incorporating animal social context in ecotoxicology: can a single individual tell the collective story? Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c04528 | PDF

Lab to field: injecting ecological complexity into behavioural ecotoxicology

One of the recent goals of my work is to understand how the effects of chemical pollution may manifest under more ecologically realistic conditions. Colleagues at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and I are incorporating technologies like acoustic telemetry and biologgers (e.g. heart rate, temperature and 3D acceleration), in combination with slow-release chemical implants to measure the impacts of pharmaceutical exposure on animals in the field. We are also exploring the spatial interactions between animals and contaminants. In other words, can movement phenotypes of animals predict both contaminant uptake (i.e. bioaccumulation) and sensitivity (i.e. behavioural or physiological response)? Together with my colleague Jack Brand, I have developed a conceptual framework for the spatiotemporal dimensions of wildlife–pollution interactions and outlined a number of key hypotheses, alongside laboratory and field-based approaches to test them.

- Brand JA*, Martin JM*, Michelangeli M, Thoré ESJ, Sandoval-Herrera N, McCallum ES, Szabo D, Callahan DL, Clark TD, Bertram MG, Brodin T (2025) Advancing the spatiotemporal dimension of wildlife–pollution interactions. Environmental Science & Technology. DOI:10.1021/acs.estlett.5c00042 | PDF *Co-first

- Brand JA, Michelangeli M, Shry SJ, Moore ER, Bose APH, Cerveny D, Martin JM, Hellström G, McCallum ES, Holmgren A, Thoré ESJ, Fick J, Brodin T, Bertram MG (2025) Pharmaceutical pollution alters river-to-sea migration success in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Science. DOI:10.1126/science.adp7174 | PDF

Evidence synthesis

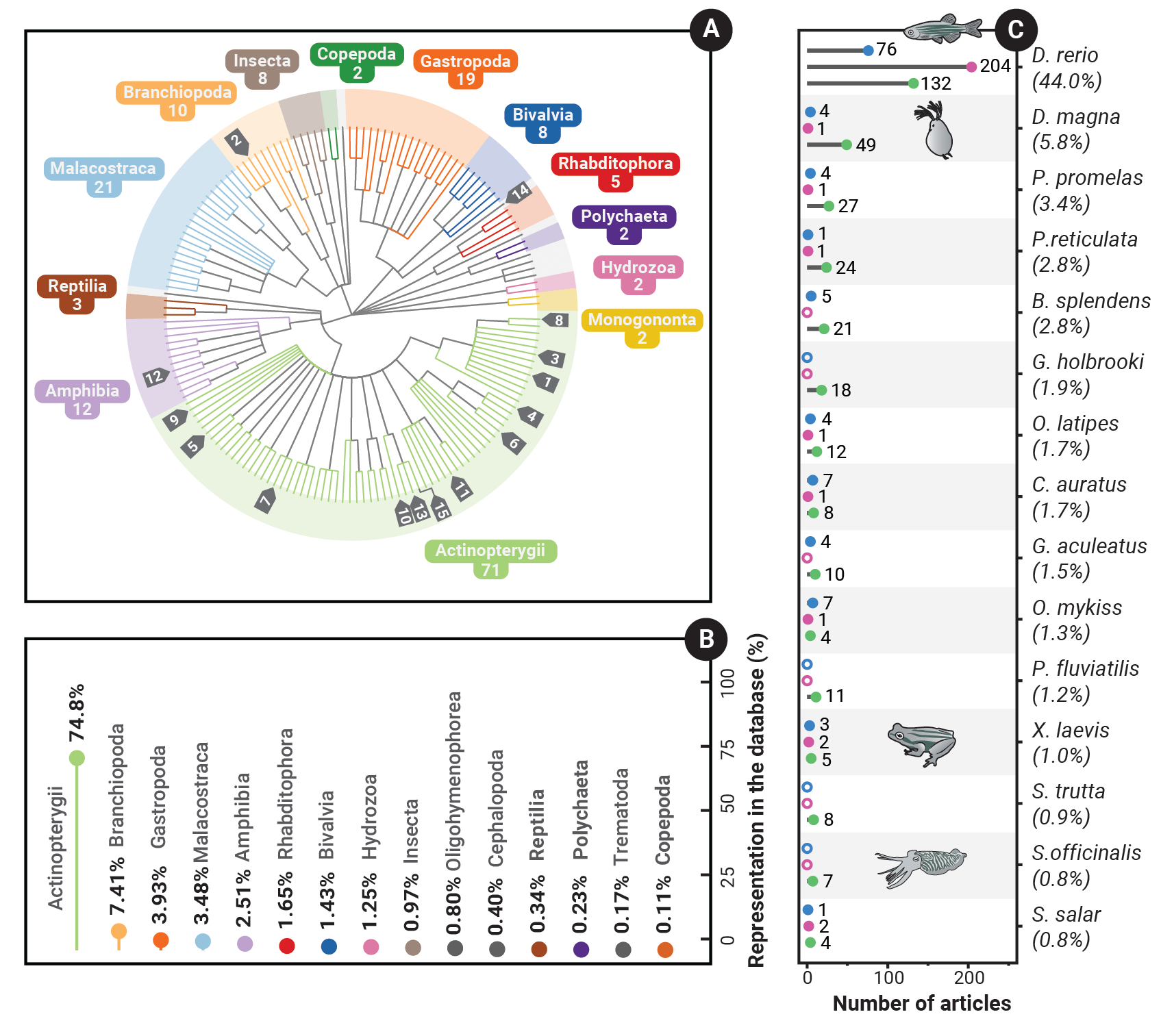

In addition to my experimental research, I employ evidence synthesis to understand the effects of emerging pollution on wildlife. Evidence synthesis is the process of collating and combining data from multiple sources to establish an evidence base, identify gaps in knowledge, and analyse overall or absolute effects. Typically, this takes the form of systematic literature reviews and meta-analysis.

Evidence synthesis is particularly important for research measuring the impacts of environmental impacts. For our research to accurately inform policy, we must first build an evidence base, and must do so in a repeatable, transparent, and unbiased manner. To this end, my team and I recently conducted a large-scale systematic map, addressing the effects of human and veterinary pharmaceuticals on aquatic animal behaviour. In this project, we identified and screened 5,988 articles, of which 901 were included in the final database, representing 1,740 species-by-compound combinations and over 48 years of data (1974–2022). To access the database and read more about this project, visit the EIPAAB database page here

- Martin JM, Bertram MG, Blanchfield PJ, Brand JA, Brodin T, Brooks BW, Cerveny D, Lagisz M, Ligocki IY, Michelangeli M, Nakagawa S, Orford JT, Sundin J, Tan H, Wong BBM, McCallum ES. (2021) Understanding the impacts of pharmaceuticals on aquatic animal behaviour: a systematic map protocol. Environ. Evid. DOI:10.1186/s13750-021-00241-z | PDF

- Martin JM, Michelangeli M, Bertram MG, Blanchfield PJ, Brand JA, Brodin T, Brooks B, Cerveny D, Fergusson KN, Lagisz M, Lovin LM, Ligocki IY, Nakagawa S, Ozeki S, Sandoval-Herrera N, Kendall S, Sundin J, Tan H, Thoré E, Wong BBM, McCallum ES (2025) Evidence of the Impacts of Pharmaceuticals on Aquatic Animal Behaviour (EIPAAB): a systematic map and open access database. Environ. Evid. DOI:10.1186/s13750-025-00357-6 | PDF

- Martin JM, Brand JA, McCallum ES (2025) Aligning Behavioural Ecotoxicology with Real-World Water Concentrations: Current Minimum Tested Levels for Pharmaceuticals Far Exceed Environmental Reality. EcoEvoRxiv. DOI:10.32942/X2F647 | PDF

Host-microbiota interactions

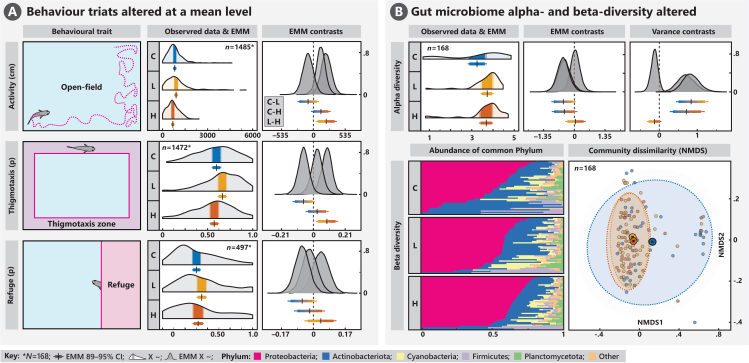

The relationship between an animal host and its microbiome is a rapidly expanding area of research in the Life Sciences. Recent evidence has established strong links between the gut microbiome, host homeostasis, and behaviour. An animal’s microbiome resides at the interface between the host and its environment; in essence, the microbiome represents a buffer and first line of defence against contaminants and environmental stressors. Importantly, aquatic animals are now exposed to a myriad of pollutants with the potential to disrupt the gut microbiome–host symbiosis.

My most recent research theme, and the subject of my Swedish Research Council funded program—Antibiotic rivers—is to understand the impacts of chemical pollution on the gut microbiome of exposed wildlife, and the consequences for their metabolism, growth, and behaviour. My preliminary results suggest that pharmaceutical exposure can cause perturbation of the gut microbial community at environmentally realistic levels, which appears to be linked to changes in neurotransmitter expression in the gut and brain.